Astronomical treasure: a 5,500-year-old clay tablet found in King Ashurbanipal’s underground library in Nineveh during the 19th century.

Sir Henry Layard unearthed an ancient “document” in modern-day Iraq that provides previously unheard-of insight into astronomical measurements made in ancient Mesopotamia over 5,500 years ago. Long thought to be an Assyrian tablet, computer research has shown that it actually has much older Sumerian origins when compared to the sky in Mesopotamia around 3300 BC.

The tablet shows the “Astrolabe,” the oldest known astronomical device. It is made up of a segmented disk-shaped star chart with lines around the edges for all the possible angles to measure. For over 150 years, the old clay tablet kept in the British Museum has puzzled researchers. “The Planisphere” is the name given to Cuneiform tablet No. K8538 in the collection of the British Museum. (Reference)

An incredible incident happened about 5,600 years ago at Köfels, Austria, when a kilometer-long asteroid impacted with the Alps. Sadly, owing to damage from Nineveh’s sacking, a sizable piece of the planisphere on this tablet—roughly 40%—is lost. There is no writing on the tablet’s back.

After determining the tablet’s astronomical relationship in 1880, Archibald Sayce and Robert Bosanquet dubbed it “Astrolabe.” Content study began with Leonard William King’s creation of an image replica of the tablet. His work was released in 1912.

He did not translate the facsimile writing signs into contemporary language, but the image facsimile of the cuneiform writing signs is fully transliterated. In the hopes of discovering other astronomical tablets with further information, he joined an archaeological expedition to the same location at Nineveh, but nothing of any use was ever discovered. King surmised that K8538 depicted the night sky over Nineveh and was a “Planisphere.”

In 1915, Ernst F. Weidner published his study on K8538, three years later. Despite his best efforts, he was unable to comprehend any of the eight separate tablet portions that were spread across the six pages of the book. It was, in his words, “magic.” He rejected King’s name “Planisphere” since the star distributions on the tablet do not match those in the Nineveh sky.

Twenty years later, two authors—Alan Bond and Mark Hempsell—made notable progress. In the book’s preface, they state that, prior to 2008, “this unique tablet [which] might relate to an impact of a Near Earth Object has never been the subject of a comprehensive and consistent translation.” (Reference)

Reinterpreting the cuneiform writing, they asserted that the tablet documented the Köfels’ Impact, an ancient asteroid strike that occurred in Austria approximately 3100 BC. Within the archeological community, this created a commotion.

It has been a mystery ever since the enormous landslide was first studied by geologists in the 19th century. It has a five-kilometer radius and is 500 meters deep. It lies in Austria, close to Köfels. In the mid-1900s, scientists concluded that it had to have been created by a massive meteor impact because of the crushing pressures and explosions they had observed.

Köfels does not look to modern eyes like an impact site should because it does not have a crater. That being said, the notion that it is just another landslide fails to explain the data that perplexed the earlier scientists. What connects the intricate Sumerian star chart discovered in the underground Nineveh library to the mysterious impact that occurred in Austria?

Because the clay tablet has depictions of stars and names of known constellations in the text, it may be studied to establish that it is an astronomical work. After over a century, no one has provided a convincing explanation for what it is, despite the fact that it has attracted a lot of attention.

With the use of modern computer techniques that can replicate trajectories and reproduce the night sky from thousands of years ago, the researchers have deciphered what the Planisphere tablet is hinting to. An anonymous observant Sumerian astronomer chose to record the occurrence on his astronomical lookout tower because he saw its historical significance and constructed the K8538 observation tablet. He was called “Lugalansheigibar – the great man who observed the sky” by Bond and Hempsell.

Like any other night, half of the tablet tracks planet positions and cloud cover; the other half, however, tracks an object big enough to record its shape while it’s still in space. Its course with respect to the stars was precisely documented by the astronomers, and this is consistent with an impact at Köfels within one degree of inaccuracy.

According to the observation, the asteroid has a diameter of more than a kilometer and was originally in an Aten type orbit around the Sun, which is a class of asteroid that orbits in close proximity to Earth and is in resonance with Earth’s orbit.

It is because of this trajectory that Köfels does not have a crater. Since the asteroid’s entering angle was so low—just six degrees—it was able to pierce the Gamskogel mountain above Längenfeld, which is 11 kilometers from Köfels. This caused the asteroid to detonate before it reached its final impact spot. As it descended the valley, it expanded to a fireball five kilometers wide (the size of the landslide).

It was no longer a solid object when it struck Köfels, thus the tremendous pressure it exerted crushed the rock and caused the landslide instead of leaving a typical impact crater.

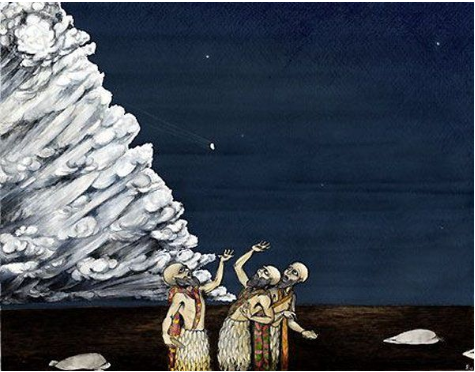

When speaking about the Köfels incident, Mark Hempsell stated: “The trajectory leads to another conclusion. Over the Mediterranean Sea, the mushroom cloud—the explosion’s rear plume—would bend and reenter the atmosphere over the Levant, Sinai, and Northern Egypt.

Even with its brief duration, the subsurface heating would be sufficient to set fire to any combustible substance, including clothing and human hair. The impact blast likely claimed the lives of more individuals beneath the plume than in the Alps.

The K8538 is an extremely uncommon scientific observation tablet that offers comparison data to support more accurate predictions of the destruction caused by asteroids and the ensuing massive droughts on Earth. The Sumerian astronomer Lugalansheigibar created this priceless document, which is currently under the care and protection of the British Museum.